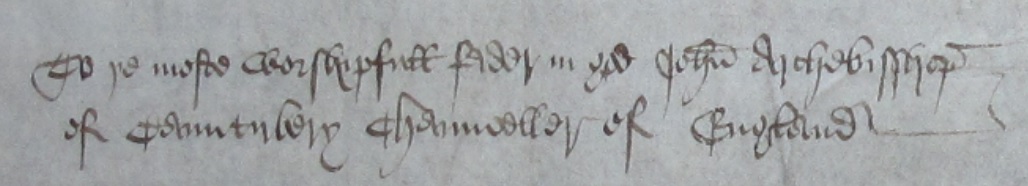

A late-medieval lady like Joan Beauchamp

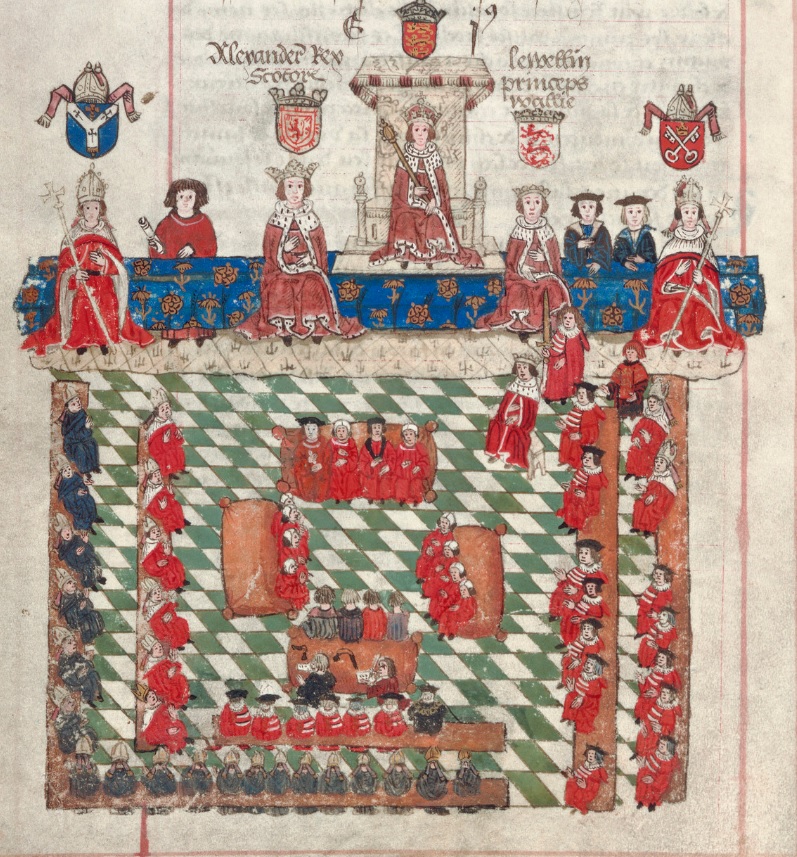

In 1432, a great lady appeared at the bar of the House of Lords. For my money, it was the trial of the century. She came with a first-class legal team of several serjeants-at-law (medieval QCs), with a train of juniors and pupils, attorneys (solicitors) and clerks. Sitting in judgment of her, the whole of the House of Lords (46 lords spiritual including abbots, 32 lords temporal, 11 law officers and justices including the Lord Chief Justice and the Attorney General). The parliament also included 266 members elected to the House of Commons but they would take no part in her trial.

In truth, Joan Beauchamp’s trial was not even the most important issue at that parliament, in the eyes of those who summoned it. Without going too deep into the politics of early 1430s England, the king Henry VI (son of Henry V of Agincourt fame) was only 10 years old. He had recently returned from France where he was crowned King of France in Paris as a result of the Treaty of Troyes. The king’s uncle, Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester, was in control of the government at this time, and as always during the Hundred Years War, the government needed money. In 15th-century England, if the perpetually-broke monarch needed money, they needed to summon a parliament to get the Commons to agree to grant taxes. It was an accepted constitutional principle in the 15th-century that the king should “live of his own” (get by on the revenue from his estates, and various feudal rights and dues as lord paramount) and that he should only resort to direct taxation, granted by parliament, in times of war or national emergency.

Nonetheless, I believe Joan’s trial is the most interesting event in this parliament. So what was the cause that brought this great lady to the bar of the House of Lords, for indeed she was great. Her income stood at £2,000 a year, easily placing her in the top 10 richest aristocrats in the realm. While in law a mere baroness in right of her dead husband, William Beauchamp (Baron Bergavenny), she was in fact by birth a FitzAlan. This family, the FitzAlan Earls of Arundel, were close relatives of the royal family and a clan of great wealth and exalted status. When Joan’s brother Thomas, Earl of Arundel, died in 1415, a male cousin inherited Arundel Castle and the earldom peerage, while Joan and her two sisters, Margaret and Elizabeth, divided up all of the Arundel estates (manors, lands, tenements, rents, reversions, advowsons, etc). This was in keeping with the medieval principle that daughters inherited in preference to males of the collateral line.

The three sisters sued each other at various times over the next 15 years, for example in 1421 Margaret and her husband, Sir Roland Lenthal, sued Joan and her sister Elizabeth over ownership of the Castell Dynas Bran, a fabulous medieval castle built by a Welsh prince in the 1200s. Just in the west Midlands and Welsh Marches, along with Abergavenny Joan owned the castles of Dynas Bran, Ewyas Lacy and Weoley. Joan proved obsessed with acquiring, maintaining and expanding her land holdings and wealth her entire life, and maintaining the force of soldiers and supporters required to protect such holdings in the late-medieval period. But I do not judge her; her attitude was typical of male aristocrats of the era. Joan, in official documentation, was known as “the King’s kinswoman” due to her connection to the king through her aunt, who was the grandmother of Henry V. (continued below…)

Arundel Castle – Birthplace of Joan Beauchamp née FitzAlan

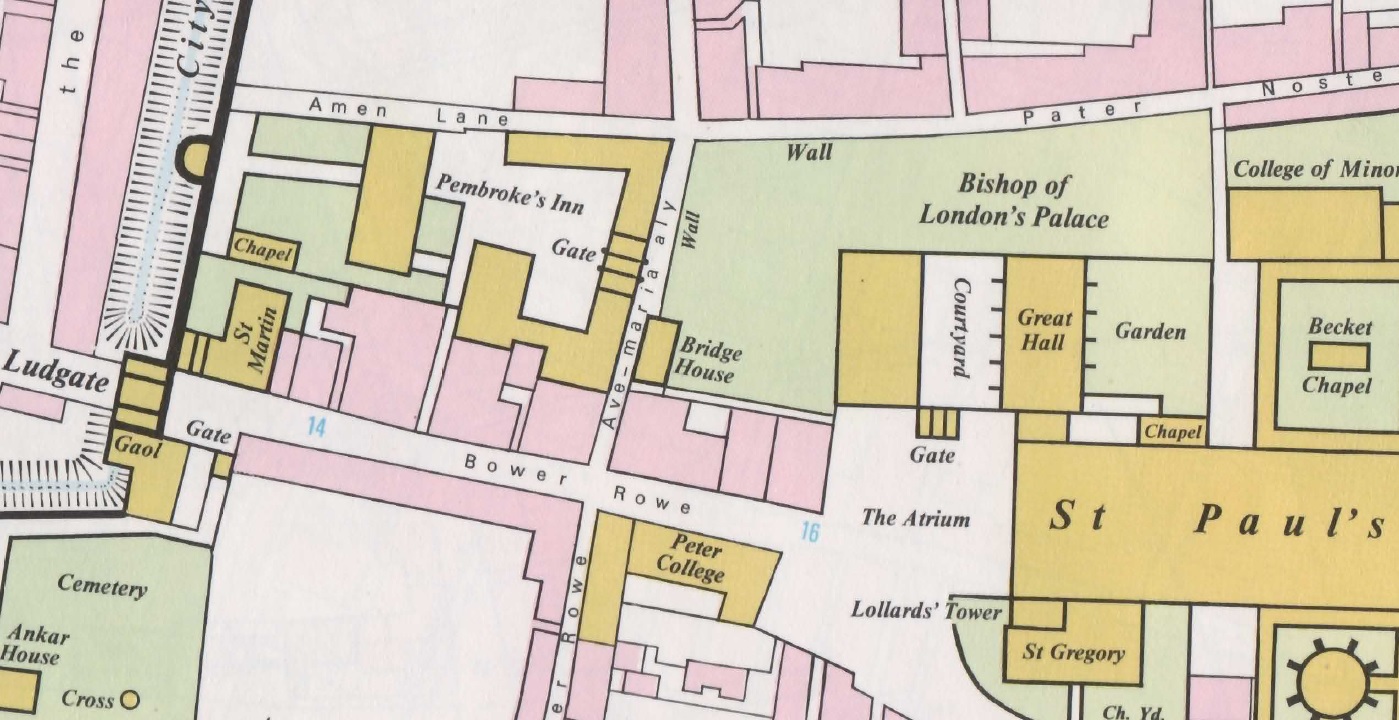

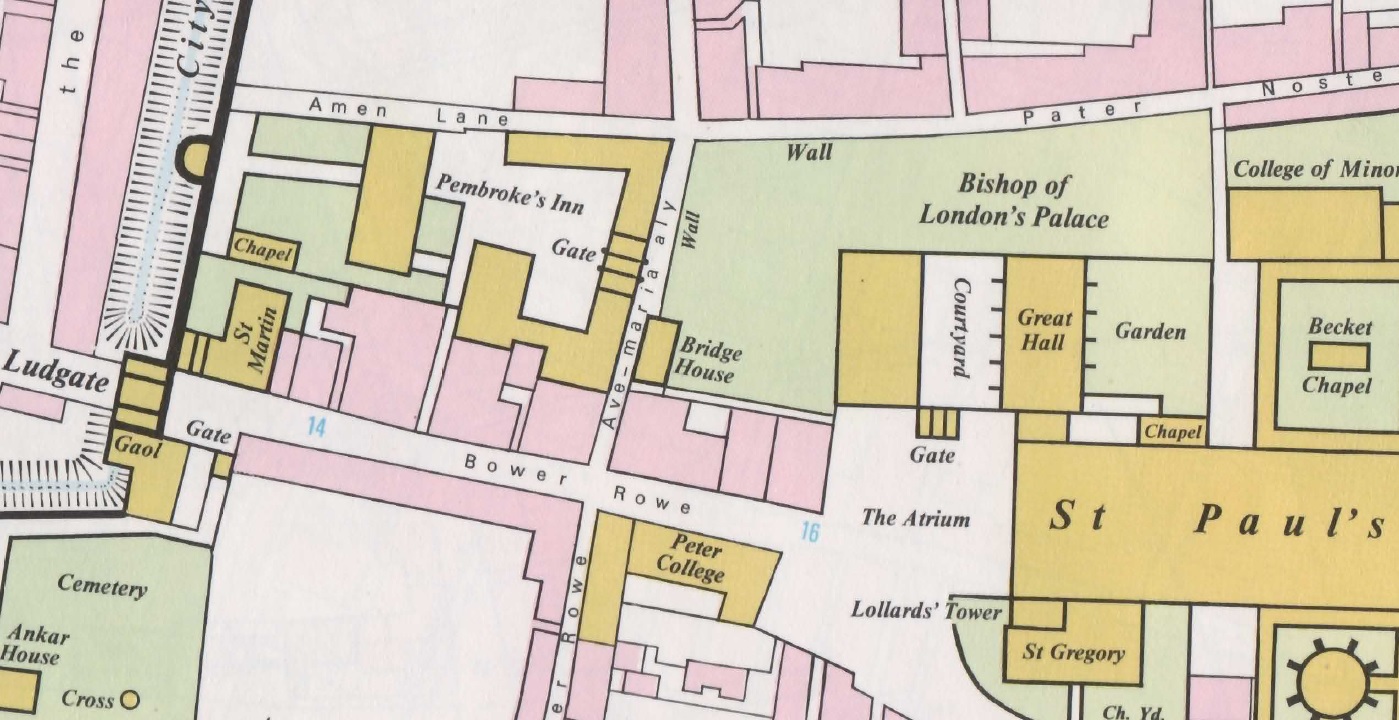

Joan’s wealth came from a number of sources. Her husband, William Beauchamp, Baron Bergavenny, was 30 years older than her and died in 1411. Unusually, she never remarried and thus retained full legal independence in ownership of property and legal personality as a “femme sole”. Upon his death, Joan inherited a life estate in survivorship in the entirety of the vast Barony of Bergavenny (rather than the usual widow’s one-third), along with the town of Abergavenny, castle, manors and lands appurtenant to the lordship and rights as a ‘marcher lord’. This was put in place by a conveyance she executed in 1408 with her husband which gave her a full life estate in the barony and in Beauchamp’s lands, and her son was never recognised or summoned to parliament as Baron Bergavenny in his lifetime, while Joan was referred to as the “domina de Bergavenny” (Latin feminine for lord, ‘dominus’). She also had from 1415, as mentioned above, the FitzAlan inheritance and also lands from her mother’s family, the De Bohuns and, apparently, from her grandmother Elizabeth de Badlesmere. The main geographic domain of her estates was the West Midlands and Welsh marches. She owned manors and estates in land in Worcestershire, Warwickshire, Herefordshire and Staffordshire, as well as Welsh lands around Abergavenny. But Joan also held manors and estates in other places too; she held estates in Buckinghamshire, Leicestershire, Norfolk, Hertfordshire, Essex and Huntingdonshire, a third share of the castle and barony of Lewes, and had a residence in London called Pembroke’s Inn, a ‘castellated’ townhouse just across the street from St Paul’s Cathedral and the Bishop’s Palace.

About 150 years after Joan’s time, Pembroke’s Inn was purchased by the livery company, the Stationers. Their guildhall not only still stands on that site today, but it follows the same outlines, including where the gatehouse is/was located, and even that little passageway down to Bower Rowe (now called Ludgate Hill).

Joan was fastidious, conscientious, even vicious, in protecting and enforcing her legal rights. She attracted the appellation “the Second Jezebel” from the chronicler Adam of Usk on account of an incident in 1404, when she was 29. She had three men on the Bergavenny estates hanged, without trial or jury process, upon accusation of theft. It is possible that the barony of Bergavenny had “marcher” lord (i.e. they were like petty kingdoms, and could exercise many powers that the king held elsewhere) rights that legally permitted this, and that this hanging was legal. Nonetheless, the locals were deeply aggrieved and it provoked an uprising in which her husband’s chief steward was killed. It should also be kept in mind that this was during the period of the uprising of Owain Glyndwr, during which Joan and her husband were besieged twice in Abergavenny Castle. The Welsh rebels managed to penetrate into the bailey/town, but not into the keep. The hanging of the thieves may be an early indication of Joan’s character. One historian asserted she ruled her estates with an “iron fist” and I believe the evidence bears this out.

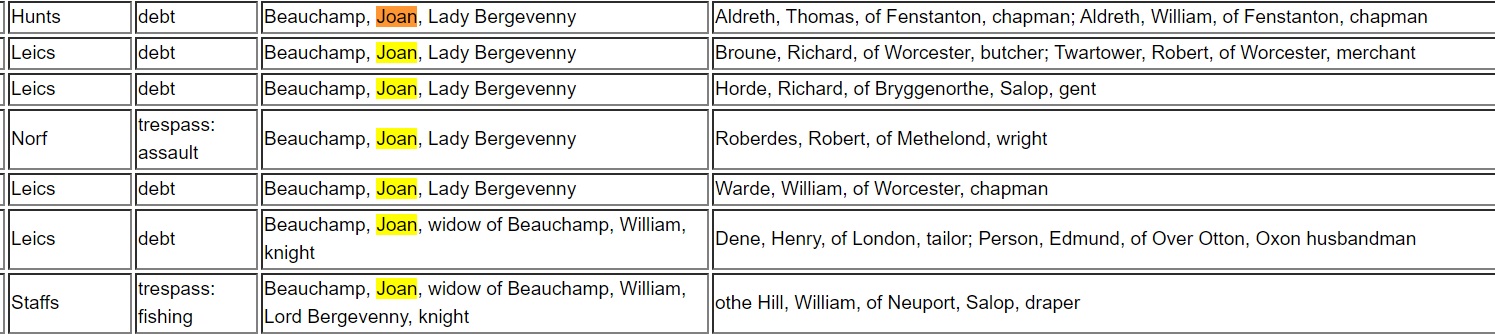

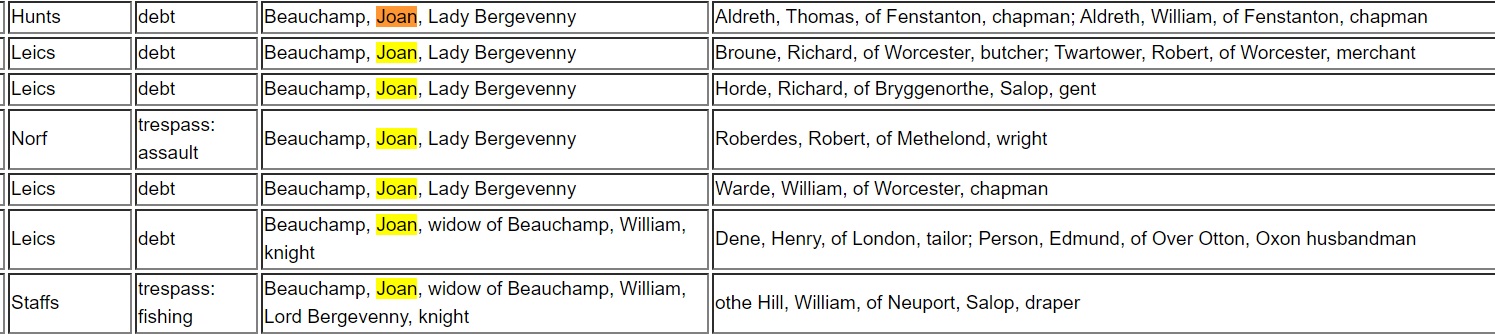

Here below is a list of cases in which Joan was a plaintiff (“claimant” since the Woolf “reforms”) in the Court of Common Pleas in Hilary term 1425. It is but a small part of the 87 different lawsuits I’ve identified between 1411 and 1435 in which Joan was a party (and this is only a proportion; there are further such lawsuits as yet unidentified).

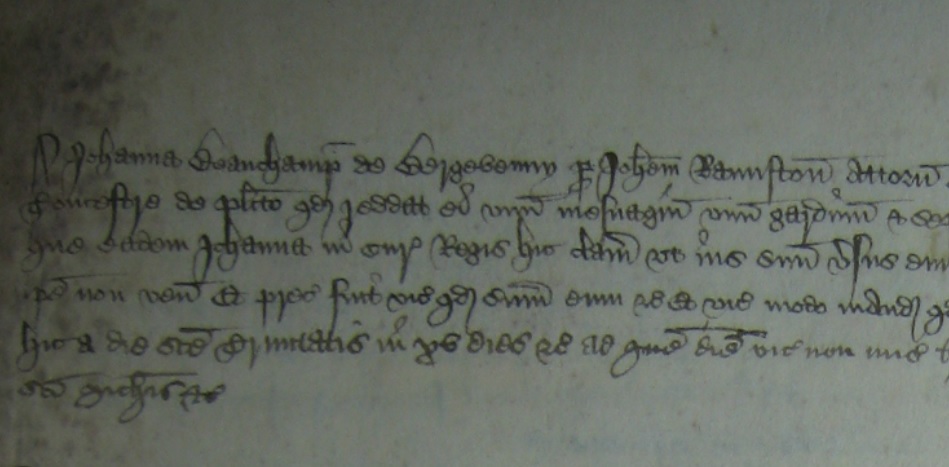

Another case in the Common Pleas from 1432 and Joan is seeking to evict one Richard Smith with a writ of cessavit and recover “unum mesuagim unum gardinum et septem acras” (a house, a garden and seven acres), on the basis of non-payment of rent;

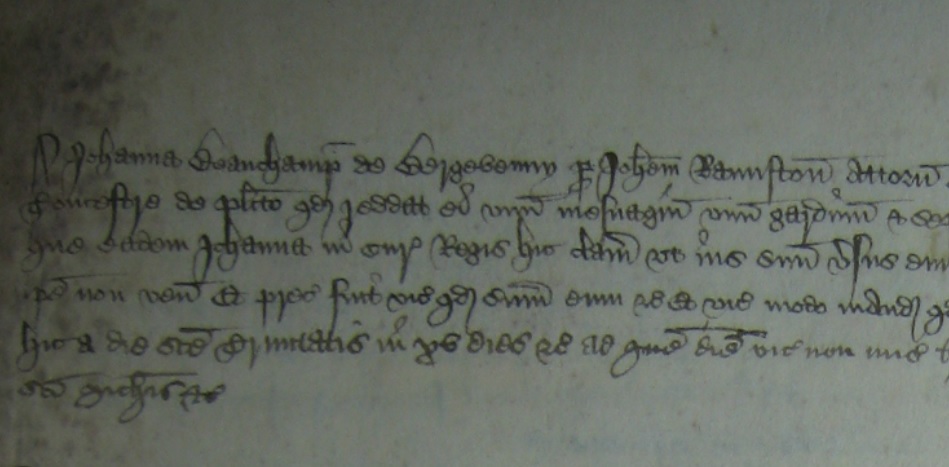

“Johanna Beauchamp de Bergavenny per Johem Banuston attorn”; Joan Beauchamp by her solicitor John Banniston appears against Richard Smith, seeking possession

I’ve checked other years between 1415 and 1435 and in any particular legal term, Joan would typically have five to ten legal cases in process at any one time. This is comparable only to the greatest magnates, and indeed a greater number than some earls and dukes. I cannot condemn Joan for seeking to evict a tenant who had not paid his rent, but this is all to say that Joan was an extremely active and aggressive, even sophisticated, litigator and knew the courts well. I will now circle back around to the main story.

The cause that brought Joan to stand at the bar of the House of Lords was a melee, perhaps better described as a battle, that occurred in Birmingham in 1431. I will first let Joan tell her own story of the events, although I caution you, just as you would never accept a claim form at face value or pass judgment before seeing the defence, do not take this story at its face value. It was a petition to the king-in-council, undoubtedly drafted by her lawyers. It reads as follows;

Joan Beauchampe, Lady Bergavenny, states that on 17 March in the king’s ninth year, she was travelling from London to her home in Harvington, and was ill at Birmingham, Edmund, Lord Ferrers of Chartley, attacked her and her servants with a large number of men of his affinity, arrayed for war and in the manner of an insurrection, against the king’s peace, laws and statutes, severely wounded several of her servants with arrows, and killed John Brydde, one of her valets de chamber. She requests a writ summoning Edmund before the Guardian and council, to be examined on these things and to have justice done to him. She also asks that he might give a surety to keep the peace towards the petitioner and her servants

Poor Joan, peaceably travelling home to her moated manor house at Harvington (see below) when she was viciously, and without cause, attacked by this Lord Ferrers. It appears that those who witnessed the battle, for it was indeed a battle between two groups of men, in armour, with weapons (like two different motorcycle gangs, the Hells Angels and the Bandidos, arriving in town and a fight breaking out), those witnesses described it somewhat differently. It seems that Joan was the instigator, and indeed we know that at this time (and for years beforehand), Joan had battled to become top dog and premier magnate in her power base of the West Midlands and Welsh marches, and particularly in eastern Warwickshire. (continued below….)

Harvington Hall, a moated manor house of medieval origin

The government in London had seen enough of Joan’s intemperance and violent ways. Or perhaps Joan’s kinship to the king was insufficient to overlook this, and the patron of Lord Ferrers, the Earl of Warwick (her dead husband’s cousin), simply had more pull at court at the time. He was indeed a war hero and considered an exemplar of chivalry. A writ was issued to Sir Humphrey Stafford, sheriff of Warwickshire, to bring Joan and others named before the King’s Bench on the Quindene of Holy Trinity [18th June, 1431], to answer for the following crimes;

before the feast of Ascension in the seventh year of our reign [3 May 1429] at Fillongley in the said county of Warwick [Joan Beauchamp] encouraged, incited and procured Thomas Michell, Richard Cokyn and Thomas Yerdeley to beat and injure John Smyth of Lichfield; and that the same Thomas, Richard and Thomas, by the abetting, incitement and instigation of the same Joan as mentioned above, made an attack on the aforesaid John Smyth at Birmingham in the said county of Warwick on the said Tuesday in the aforesaid year and beat and injured him so that he feared for his life, and inflicted other enormities on him against our peace; and that William Lee, Henry Brokesby, Henry Felongley, John Ryder, Thomas Russell, John Seggesley, Meredith Walshman, Thomas Fauconer, Thomas Yerdeley, John Loudham, John de Wyrley, Henry Cooke of Weoley, Alexander Shefeld, John Chewe, John Morys and many others by the abetment, incitement and instigation of the aforesaid Joan, at the aforesaid Birmingham on Saturday in the fourth week of Lent in the ninth year of our reign [10 March 1431] with force of arms, namely with swords, sticks, bows, arrows, shields, iron helmets, palettes and other armour, made an attack then and there on Thomas Peynton, Richard Arblastre, John Cutte, John Glover, William Squyer, John Cooke, John Fraunceys, William Stretton, Hugh Roggeres, John Penford, Richard late servant of Richard Walrond, John Necheles, John Lord and many others, and beat, injured, maimed and maltreated them so that they feared for their lives and inflicted other enormities on them against our peace

As I have previously described, Joan was a major force in the West Midlands and in response to the above writ, Sir Humphrey dithered. This wasn’t out of some respect for an exalted and respectable lady. He presumably feared her. He returned the writ saying that certain senior servants of Joan’s named on the writ couldn’t be found or were already dead. Upon the return of the writ the King’s Bench actually fined Sir Humphrey 100 shillings (£5) for this failure to do his duty as they found this unsatisfactory, although I can entirely understand Sir Humphrey’s circumspection in his dealings with the Tony Soprano of 15th-century Warwickshire.

The writ that was issued above required them to appear before the King’s Bench on 18th June, 1431 to

“to show whether they have or know of anything to say for themselves, namely, whether the aforesaid £1,200 granted by aforesaid Joan from her lands and chattels as stated above, and if they wish to say why the said £200 granted by each of the aforesaid John Barton, Richard Fox, William Aubrey and Henry Rous from the lands and chattels of each of them in the aforesaid form ought not to be rendered and levied for our benefit”

Wait, what? £1,200? Where did that come from? This requires us to take a slight detour, and a journey back in time to the distant days of 1418. I realise how circuitous this all is, but it’s vital to understand. In 1418, during the reign of the previous King Henry V, Joan was summoned before the Privy Council as a result of a disturbance of the king’s peace.

Joan had become embroiled in a dispute with the Burdet clan of Warwickshire. Sir Thomas Burdet MP, elected county knight of the shire for Warwickshire four times, and his son Nicholas, were well-known criminals and ne’er-do-wells in the shire. In the same year 1418 they were indicted for ransacking a manor and destroying a mill owned by the Abbey of Evesham (which is only 3 miles away from Baroness Joan’s house at Harvinton), although they were later acquitted before the King’s Bench (whether by jury acquittal or succeeding on an issue of law is not clear). Perhaps Joan had good relations with the abbey and was outraged by the Burdets’ conduct, although that is entirely speculation.

In any case, Joan made credible threats to have the son, Nicholas, murdered. The government in London found it necessary to step in and summoned all parties to appear before the king-in-council (although the king himself was probably in France on campaign). The records show that the council ordered that Joan be ‘mainprised’ (in essence bailed upon a surety) for £1,200 that she would not harm Nicholas Burdet “or any of our people” (the king’s people/lieges, in other words, anyone and everyone) and that if Nicholas or “any of our people” were to come to harm, or Joan “incited to be caused any bodily harm”, she would forfeit the £1,200 and six of her named servants forfeit £200 each. In reality, Joan would likely have to pay theirs, according to the standards of good lordship to your liegemen, and so it would be a total bill of £2,400 a huge sum at a time when the king’s income might be £50,000 in a year.

It would appear that one of the clever lawyers in the government remembered that Joan was so bound (and indeed, was was bound over many times to keep the peace, in different disputes, including one in which she was bound to arbitration of the Duke of Bedford in a dispute where she had already had Lord Talbot’s brother-in-law killed, and required to give assurances that she would do no further harm to Lord Talbot or his family). This government lawyer presumably saw that they could rely on the “any of our people” clause from the 1418 mainprise and recognisance to require Joan to pay the £1,200 for the Birmingham melee.

On 18th June, 1431, Joan’s solicitor William Sonde appeared before the king’s bench. For the government, a crown prosecutor was instructed, up-and-coming barrister and Warwickshire landowner Thomas Griswold, appeared for the king upon a writ of scire facias. That is, a writ that is basically “show cause why/why not X”. In essence, “Show cause why you should not forfeit the sum of £1,200 for harming or inciting to bodily harm ‘any of our people'”. Joan’s solicitor, Sonde, traversed the pleadings, asserting that Joan was not guilty of inciting, aiding or abetting the assault of Smith or the melee in Birmingham, nor were any of her individual servants guilty of the alleged crimes.

For these were indeed crimes. In medieval England, every felony was a capital offence. Robbery, burglary, arson, murder, battery, each would result in a death sentence upon conviction (although this was mitigated by the many and varied ‘routes’ to avoiding the noose). So it is indeed interesting that no criminal process issued, but instead a civil process.

In any case, the attorney William Sonde said that Joan would “put herself on the country”. That means that instead of alleging some legal defect and pleading a demurrer, she “traversed” the factual allegation and put herself in the hands of the jury and their verdict. Accordingly, the next day a new writ to the sheriff, Sir Humphrey, was issued by the council, personally witnessed and endorsed by the Lord Chief Justice William Cheney, as follows;

We command you that you shall not neglect on account of any liberty in your bailiwick but that you shall cause to come before us on the quindene of Michaelmas wherever we shall then be in England 24 worthy and lawful men both knights and others with view of Fillongley and Birmingham in your county by whom the truth of the matter might be better known; and whom Joan Beauchamp, Lady Abergavenny, has no association or contact with: to examine on their oath whether the aforesaid Joan on Tuesday before the feast of Ascension in the seventh year of our reign

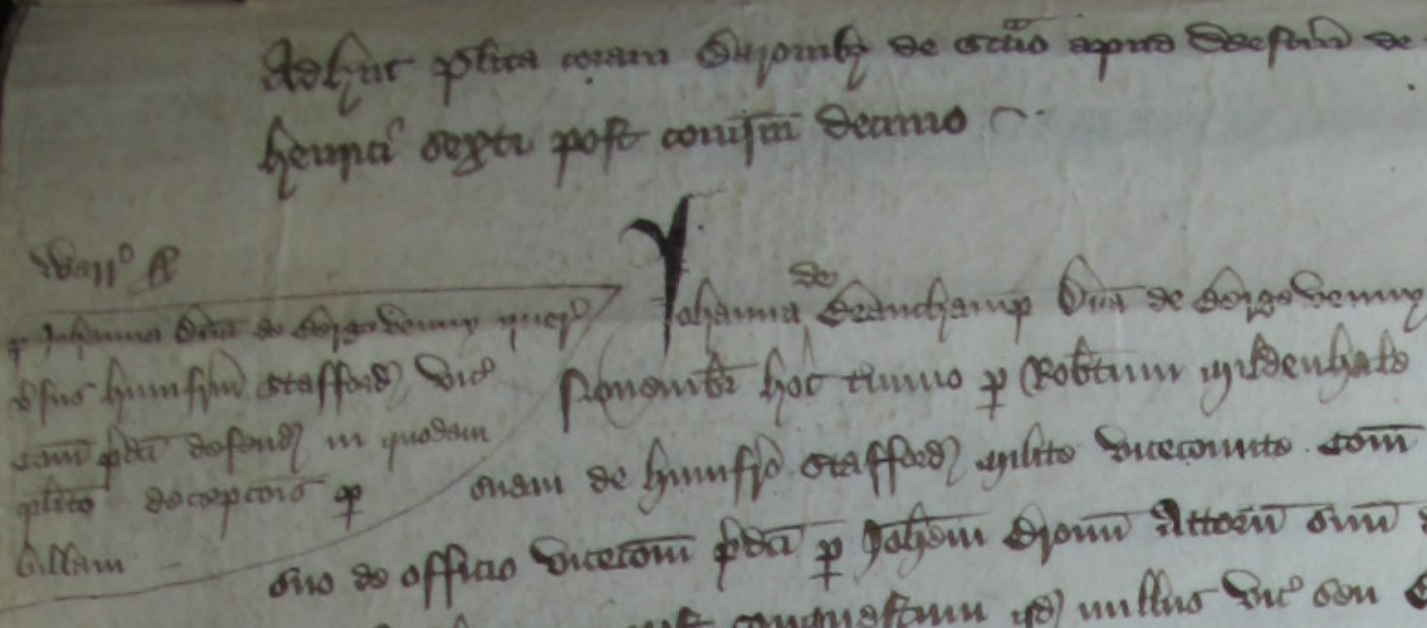

It was ordered that two juries of worthy men (2 x 12), with no previous association with Joan, should be assembled to issue a verdict on the two crimes. It should be noted that Joan owned the manor of Fillongley, and many of the jurors would be her tenants. At the same time, Joan’s lawyers pursued a tactic that 15th-century lawyers loved; a “collateral attack”. Her lawyers issued suit in the Court of Exchequer against Sir Humphrey Stafford alleging that he was conspiring against her, that he was packing a jury with her enemies. Seems rather unfair to poor Sir Humphrey, who had dithered somewhat to Joan’s benefit.

Record of the proceedings of Court of Exchequer proceedings of “Johanna de Beauchamp, Domina de Bergavenny” against “Humfre Stafford militi”

She also served a petition to the king-in-council (from which we have her side of the story, as above). There appears to be other litigation issued in the Court of Chancery as well for which I am still tracking down evidence.

As this legal hearing occurred in June and the courts were about to recess for the summer break and the end of the legal year, it was ordered that the Jury should assemble in October on the “Quindene of Michaelmas”. When the time came, crown prosecutor Thomas Griswold prosecuted both cases while Joan’s lawyers attempted to secure an acquittal. The juries duly deliberated after hearing the evidence; the jury determining the Fillongley conspiracy acquitted Joan while the jury determining the Birmingham melee found Joan guilty.

Joan was now back where she started, with a writ of scire facias pending and with Griswold now having a jury verdict that proved, at law, Joan was guilty of the inciting the Birmingham melee. Joan’s lawyers now opted for the nuclear option. While the case against Humphrey Stafford proceeded in the Exchequer and other litigation made its way through the chancery, each a “collateral attack” to attempt to frustrate process against her in the King’s Bench, Joan and her lawyers opted to make a petition to parliament and appear in person. Along with all these collateral attacks, Joan also deposited £1,000 in the exchequer as a sort-of aggressive settlement offer (it seems harder to refuse settlement when they’ve already put the money in your account, and indeed the government was short of cash).

So it transpires that the trial of Joan Beauchamp, at the bar of the House of Lords, was at her own behest; she was appealing from the King’s Bench directly to parliament. She had served petition to the High Court of Parliament, which due to parliamentary sovereignty can remedy any defect in a lower court. In addition, the House of Lords as a chamber had a quasi-judicial character, and also special jurisdiction over criminal actions against members of the peerage (which, while Joan was not a peer per se, it was argued in 1409 by Constance of York, Countess of Gloucester, that she was entitled to trial in the House of Lords in a case where she was accused of having a man abducted). Present in the chamber were the people mentioned above; 46 lords spiritual, 32 lords temporal, 11 justices and law officers including Chief Justice Cheney and Attorney-General John Vampage. We do not know the names of Joan’s representatives but we do know it consisted of multiple serjeants, who in their train would be accompanied by their juniors, pupils, as well as Joan’s attorneys like William Sonde.

The basis on which Joan’s lawyers argued for the invalidity of the judgments against her were pure technicalities. She didn’t even bother to argue factual innocence. Her lawyers submitted;

(1) In the enrolment of any recognisance, it is necessary for the place to be recorded and for the person so burdened to be present in person. They argued that it was not proven in the records that Joan appeared before in person for this matter in 1418 and that the recognisance did not record the place where it was made, and therefore “the aforesaid recognisance is insufficient in law; and whatever process has been made thereupon, and the judgment rendered thereon, are erroneous”

(2) That the writ of scire facias made before the lord king in his chancery [the government department of chancery, not the Court of Chancery] still remains in the lord king’s court [King’s Bench] never having been sent before the king himself, but the tenor of the enrolment of the security of the peace was sent by the king [a 10 year old, in reality, his council/government] to his justices by a writ of mittimus. The tenor [a summary of the facts rather than the verdict/judgment/order-in-council] is not sufficiently founded in law to warrant a writ of scire facias, and thus no process can issue from the tenor of the recognisance, rather than the original document itself, which is itself erroneous for reasons mentioned above

They made three additional legal arguments that, even for a medieval law nerd like me, are so painfully, pedantically procedural (something I usually love) that I won’t inflict them upon you (continued below…)

In medieval times, the Palace of Westminster was a rambling precinct of buildings, more like a super-sized Inn of Court or Oxbridge college. It was the home of the law courts, an archive, a royal palace, an administrative centre.

What I will relay is from the record of the parliament itself;

justices and serjeants-at-law of the lord king, and of others skilled in the law, both on behalf of the lord king and on behalf of the aforesaid Joan henceforward having been considered and reflected upon, fully heard and understood, because the court of the aforesaid parliament has not been advised to render judgment on this matter. It is therefore adjudged that the aforesaid Joan should have a day to be before the lord king in the next parliament

So after many submissions, replications, rejoinders, discussion of law and procedure, the outcome was that the council not explicitly requested the lords to give judgment, and so it adjourned to the next parliament, which occurred in 1433. The judgment in the next parliament was to ratify a settlement; the government accepted the £1,000 Joan had previously deposited before agreement, and in exchange Joan would keep the peace, cease any process in the courts, and file and serve a quitclaim for Sir Humphrey Stafford immunising him against any claims in this matter.

The Big Question

So, it all turned out to be a bit of an anti-climax. The interesting question, for me, is whether the “Second Jezebel” was being punished, whether she was judged harshly because she was a woman, whether the government proceeded against her because she was an aggressive wealthy landowning woman in a man’s world. The conclusion I have come to is no. If anything, the “king’s kinswoman” as she was called in official documents, enjoyed exceptional favour and protection, and in many ways was treated as if she were a man in the same position, in terms of wealth and status.

Joan was commissioned to undertake special missions by the government, for example in 1419 a commission was issued out of the privy council;

“Commission to the King’s kinswoman Joan, lady of Bergavenny, to seize all gold, silver, things, goods and jewels of any kind under the keeping of Friar John Randall lately dwelling in the house of the order of Friars Minor in Shrewsbury, or committed by him to any other person to keep, and bring them before the king and council”

This was a politically sensitive mission. Friar John Randall was an astrologer and personal confessor of the then King Henry V’s stepmother, Queen Joan (of Navarre). It seems they wanted to find evidence of sorcery or the like. Queen Joan was in any case accused of witchcraft and put under house arrest, all her property was confiscated. She was released and her property returned upon Henry V’s death in 1422. Many have asked why Henry V treated his stepmother this way. What is notable for our purposes is that Joan Beauchamp was commissioned to seize all of the possessions (particularly, perhaps, letters or books, or occult charms) of the friar in a case of exceptional political sensitivity. She was a trusted relative of the king. This was only a year after she was bound over to keep the peace in the Burdet dispute.

There are other indications of royal favour. After Joan’s brother died and she and her sisters inherited the Arundel estates, the privy council issued an order to the treasurer and barons of the Exchequer “not to trouble Joan de Beauchamp for her homage”, that she and her sisters were to be considered full heirs to the Arundel estates and the king had received his homage and a fine paid into the hanaper. Further claims by the male cousin went nowhere.

In 1422, when the crown went to the aristocrats and gentry of England for a “forced loan”, Joan was appointed commissioner for Worcestershire to pursue aristocrats and gentry for their share. In the list of commissioners there were dozens of men, and only two women, one of which was Joan. In short, she was a trusted magnate who could be relied upon by the government. However, she was also a well-known troublemaker. You’ve seen the incidents above, from the hanging of the three accused thieves without due process, to the apparent threat to have Nicholas Burdet murdered, to the Fillongley conspiracy (acquitted, I concede) and the Birmingham melee.

The same year Joan was commissioned by the privy council to seize the belongings of Friar Randall, she was also cited for another dispute in the patent rolls, July 15, 1419;

Order, by advice of the council, because of certain strifes and dissensions have arisen between Joan, Lady of Bergavenny, and John Skymore, ‘chivaler’, on one [side], and Isabel late wife of Thomas Wallaweyn, Richard Wallaweyn and Richard Pecoke, executors of the will of Thomas Wallaweyn, on the other [side], about the right, title and possession of the manor of Langeford, county Hereford, the manor shall remain in the king’s hands and John Merbury shall have the keeping of it in the king’s name until All Saints next

In 1426, in the Chancery (the government department of chancery, not the Court of Chancery) close rolls, Joan was cited for the Talbot affair;

Joan Beauchamp, lady of Bergavenny, to John Duke of Bedford [king’s uncle and regent]. Recognisance for £1,000.

Condition, she shall abide and perform the award of the duke [i.e. arbitration] touching debates, quarrels, pleas, controversies, demands, etc, between her and her men, tenants and servants and John, Lord Talbot, and Hugh Cokesay, knight, their men, tenants and servants, by reason of any criminal and personal action, and especially the manslaughter of William Talbot, knight, brother of John Talbot, so that the award be made before the [Feast of] Purification next. Proviso that … [Joan] she shall do or procure no hurt or harm to John Talbot, his tenants or servants, in the mean time.

People didn’t respect Joan. They were scared of her. She repeatedly appears in legal documents as being involved in violent quarrels over lands and manors, repeatedly has to be bound over to keep the peace, and yet was accorded respect by the government and king, given special missions, and at the parliament of 1433 got a bit of a sweetheart deal and in doing so saved herself over £1,500.

Motivations

Joan didn’t necessarily have an easy life, in the personal sense. Her mother died when she was 10. When she was 17, she was married off to a 50 year old man, William, Baron Bergavenny and when she was 22 her father was executed by Richard II for treason. He was beheaded (although Joan’s aunt, Joan de Bohun, Countess of Hereford, obtained revenge for the family when, during the Epiphany Uprising against Henry IV, Richard II’s half-brother John Holland, and accomplice in the murder of Joan de Bohun’s brother, Joan Beauchamp’s father, was found by Joan de Bohun’s soldiers at her castle of Pleshy. Joan ordered her soldiers to bring up a block and behead Holland immediately, for which she was rewarded with Holland’s Thames-side mansion, Coldharbour).

Joan Beauchamp had two children, Richard who died in 1422 and Joan II who died in 1430. Joan herself died in 1435. I can’t imagine how awful it would be to lose a mother so young, your father beheaded, to be predeceased by both your children. (continued below…)

Joan’s husband, William, Baron Bergavenny

Joan Beauchamp was clearly acquisitive and violent. In that sense she was not different from many aristocrats and gentry of the 15th-century although she seems to outpace many of her male contemporaries in just how vicious and inclined she was to the use of violence and litigation. But she was also known to be pious and generous to the poor, although in fairness that was fairly conventional religiosity of the time and expected of men and women of her station.

Clearly she was a complex character. She deserves a biography. In some respects she reminds me of Elizabeth I, who also lost a parent at a young age who was also killed by beheading, shied away from marriage (while Joan, unusually, never remarried), was very focused on ensuring the security of her estate and station as queen. While Elizabeth I opted for security in the love of her people, and her popularity, Joan Beauchamp opted for the “iron fist” in an age when that was not unusual.

What I do know is that the fact it took until 1431 for Joan to be fundamentally called to account by the law suggests she was not persecuted. She was not punished as a Jezebel, an unruly woman in a man’s world. Her social class and status, and her loyalty to the Lancastrian dynasty to whom she was closely related, clearly mattered much more than her sex in determining the way society dealt with her. What of women who were not quite as well-off, not quite as well-connected and exalted as Joan? It’s a subject I’m pursuing in research and I think is worthy of considerably more attention that it has received academically.

What it can teach modern lawyers

I do believe there are lessons to be learned by modern lawyers from the tactics of medieval lawyers. Collateral attacks so beloved by medieval lawyers might find their expression in the issuing of proceedings in multiple jurisdictions/courts, the use of SARs, FoIA, and professional/regulatory body complaints to harry a defendant is how a medieval lawyer might approach (for example) an employment tribunal claim.

And perhaps more useful still, the strong focus of medieval lawyers on accurate, concise pleadings and the allowance by the court of replications, rejoinders and rebutters by each side to continuously narrow down the issues in dispute. That is something that, in an age of reduced judicial resources, might be a good way to minimise the number of issues still in dispute by the time of trial (or perhaps even lead to an early settlement). There are further lessons our medieval brethren can teach us, and my next blogpost will be on some of these topics.